Chicago, IL

August 19, 2013

The roof on top of Crane Technical High School on Jackson Boulevard in Chicago is blindingly white—so reflective that we’re squinting through our sunglasses. Installed by Knickerbocker Paving & Roofing Co., the 110,000-square-foot white roof is part of Chicago’s efforts to reverse the urban heat island effect that can make cities up to 10 degrees hotter than surrounding rural areas. From our vantage point, we can see a mosaic of light-colored roofs reflecting the sun’s rays away from the urban core.

White roofs—which can be as easy as a coat of paint or as high-tech as a the ultra-white modified bitumen membrane on Crane Technical High School—have been touted for their ability to cool buildings, providing some relief on hot days and also reducing the need for air conditioning, therefore cutting greenhouse gas emissions. They’ve been proliferating in a slow but steady wave across major cities like New York, Los Angeles, and Chicago, often as a part of climate action plans. Former Secretary of Energy Steven Chu encouraged the idea. But recent research has questioned the technology: do white roofs work?

The white roof revolution

For some, installing a white roof represents the simplest form of geoengineering, or manipulating the Earth’s climate. In cities like Chicago, the white roof craze is at least partly about climate change adaptation, or lessening the negative, local impacts of global warming. The City’s temperature has already risen by 2.6 degrees Fahrenheit since 1980. By 2050, Chicago’s climate could be more like Baton Rouge’s, with more than a month worth of 100-degree weather. Light-colored roofs might provide some relief. A 2012 study out of Yale used satellite images to determine that new reflective surfaces installed in Chicago between 1995 and 2008 raised the city’s albedo, or reflectivity, by 0.016 (albedo is on a scale of 0 to 1, with 1 being the most reflective).

On the mitigation side, research out of the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory suggests that changing the reflectivity of urban areas could also help to combat global warming by reducing the need for air conditioning. Groups like the White Roof Project in New York calculate that white roofs can save building owners up to 40 percent on their electricity bills; if all urban rooftops across the globe were white, we would avoid emitting 24 billion metric tons of carbon dioxide—equal to total world emissions in 2010.

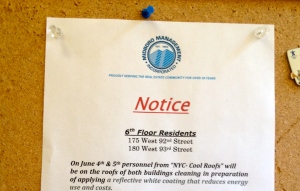

Many cities—including Chicago—therefore see installing cool roofs as the ripest of the low-hanging fruit. New York City’s Cool Roofs program aims to whiten 6 million square feet of rooftop across the city, and volunteers have painted 3.6 million square feet so far. In Chicago, a 2001 Urban Heat Island Ordinance wrote ‘cool roofs’—which include garden and photovoltaic roofs as well as white ones—into law. The 2009 rendition of the ordinance requires all ‘low-sloped’ roofs in Chicago to have a minimum reflectance of 0.72, meaning the roof reflects at least 72 percent of the sunlight it receives while absorbing no more than 28 percent. (In contrast, the dark asphalt that covers most of the world’s roofs has an average reflectance of 0.12—these roofs absorb sunlight like it’s their job.) The ordinance allows a 0.5 reflectance after the roof is three years old, and it does not apply if the roof is vegetated or very steep.

“Many businesses and building managers were installing cool roofs before the ordinance came in,” Bill McHugh, the Executive Director of the Chicagoland Roofing Council (CRC), said. “Because it is mandated for new roofs, there are many more doing it now.”

Too cool to be true?

Cool roofs might seem like a no-brainer, but as white and vegetated rooftops proliferate in urban areas, some researchers are beginning to question their effectiveness—on both the climate adaptation and mitigation fronts. A 2012 Stanford University study modeled what would happen over 20 years if all the world’s roofs were made reflective. The model, which took into account large-scale climate feedbacks, found that, with widespread white roofs, the slight cooling effect in cities would be more than offset by a warming effect overall. This warming was due in part to the fact that white roofs don’t get rid of sunlight, they simply reflect it upwards, sometimes to be absorbed by soot and other particles in the atmosphere instead. The model also found that white roofs stabilized surface air and reduced cloudiness, which in turn increased solar radiation.

The study is catching the attention of roofing experts. When we called Paul Cronin, the Vice President of Knickerbocker Roofing, to talk about the Crane Technical High School project, he emailed us a summary of the Stanford research that has been passed among roofing contractors. “We’ve installed a zillion of them [at the request of building managers and architects],” Cronin said of white roofs, “but the technology may not be as good as they think.”

And when it comes to climate change mitigation, Brian Glosik, a Project Manager at the Chicago Center for Green Technology, says that the energy-saving capacity of cool roofs may also be overhyped. In a city like Chicago, any energy savings from a light-colored or vegetated roof would only come in the few summer weeks or months when the air conditioning is on; for much of the winter, roofs are covered by snow. Roofs are a fairly small percentage of a building’s energy envelope, and for skyscrapers, the roof type only really makes a difference on the top floor. Also, a practical point: a white roof gets dirty.

And when it comes to climate change mitigation, Brian Glosik, a Project Manager at the Chicago Center for Green Technology, says that the energy-saving capacity of cool roofs may also be overhyped. In a city like Chicago, any energy savings from a light-colored or vegetated roof would only come in the few summer weeks or months when the air conditioning is on; for much of the winter, roofs are covered by snow. Roofs are a fairly small percentage of a building’s energy envelope, and for skyscrapers, the roof type only really makes a difference on the top floor. Also, a practical point: a white roof gets dirty.

“White roofs do reflect light, but they can still hold heat,” Glosik said. “Roofs are really subjective in terms of energy use. You have to know the SRI (solar reflective index) to really account for any energy benefit.”

Other reasons for rethinking roofs

Though the Stanford research prompted some hoopla over the ‘myth’ of white roofs, the major takeaway from the study is that roofs—whether white, black, hot pink, or zebra-striped—don’t make a whole lot of difference in terms of the global temperature. Only about 0.06 percent of the Earth’s surface is covered by rooftops and roads and, even with rapid urbanization, the urban heat island effect only contributes to a small fraction of global warming. From a climate change mitigation standpoint, the ‘coolest’ roof of all is probably one covered in solar panels that convert sunlight into energy—a sure-fire way to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

With the jury still out on white roofs, many building owners and architects are moving beyond the slab black rooftop for other reasons. Chicago’s climate action plan calls for installing rooftop gardens on 6,000 buildings in the city. These green, vegetated roofs absorb rainfall, reducing runoff and therefore lessening the strain on Chicago’s stormwater system. This is especially important since the city is expected to receive heavier rain and snow as the climate changes. Glosik says that stormwater management—not energy savings—is now the major reason for installing a ‘cool’ roof.

The view from Crane

But white roofs still hold a heavenly allure. From Crane Technical High School’s new, white-membrane rooftop, you can look out over the peppering of light-colored roofs in the low-income West Haven/Near West Side neighborhoods. In Chicago’s beleaguered public school system, Crane—a 100 percent minority and 99 percent economically disadvantaged high school, according to the U.S. New and World Report—has been yo-yoing on and off the list of schools selected for closure for a while. The neighborhood convinced the School Board to keep Crane open by proposing a plan to ‘phase out’ the existing school in 2013 and turn it into one focused on preparing students for health sciences jobs. It’s in schools like these, where every penny counts, that a white roof might just help to keep the students cool while saving on energy costs—or at least that’s the hope.

As Crane’s building manager led us up to the roof, he expressed the sentiment of many people in Chicago who are excited about cool roofs: “The white roof is a good thing. Without it, we’d be cooking in here.”

Amazing! Interesting story.

Pingback: How can communities reduce carbon emissions while preparing for climate change impacts? « Great American Adaptation Road Trip